|

|

OS Grid ref:

Lat/Long: 54.6799230,-3.0055320

|

‘Essential journeys only’ is still displayed on the motorway. I

returned to Mosedale and parked on the grass verge a short

distance to the west. Nearer the village the grass verge has

been churned to a muddy mess by workers vehicles working on the

adjacent farmhouse. It was overcast as I wandered north along

the road towards Quaker Hill.

|

|

There were no unfriendly locals around like last week. A woman

overtook me on an electric bike and said hello, presumably a

local. I made a detour across some very wet ground to inspect a

couple of mine adits and spoil heaps. There was no access as the

entrances were collapsed. The old map says ‘Copper Mine’. I

reached the ford and crossed by the footbridge. |

Copper Mine adit. |

|

|

Looking back along the road. |

Another view from the road. |

|

Instead of following the path through the gorse that’s shown on

the map I continued a short way and followed a well used path

with horse tracks up to the miners track. The weather had

improved and the higher part of the Carrock Beck valley was in

sunshine. It was very pleasant as I walked up to Willywood Well

which I visited last week. When I got there I decided to stop

for a while and eat one of my two sandwiches. |

Willywood Well. |

Heading up the miner's track. |

|

There was some sunshine higher up but I sat in shade. I

continued up the track to a minor branch off to the left that

headed to a ford and up Red Gate track. Carrock Beck was running

high but there was a narrow point where I could hop over. Red

Gate track continued up the hill and I soon stopped to eat my

last butty. The track continued up and was well defined due to

centuries of use. |

Looking back down Red Gate track. |

|

The views opened up and I stopped to look down on the ruin of

the smithy and across to the Driggith Mine spoil heaps. I

reached the high point on the main Carrock path and turned

right. My original plan was to head west to the Cumbria Way path

but decided to follow a faint path across to Drygill Head. I was

soon on pathless fell but the going was quite easy. |

Driggith Mine in the distance. |

I met the main path and tuned left to continue to the Ligy

Hut. So far I’d only seen walkers at a distance and still had

the place to myself. I peeked inside then left to descend

directly down to the SE. |

Lingy Hut. |

Inside Lingy Hut.

|

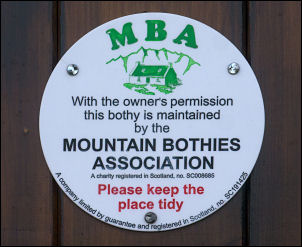

Maintained by the Mountain Bothies

Association. |

|

I continued upwards to t |

View down from the Lingy Hut. |

|

I followed the minor |

I reached the Carrock Mine aea and stopped to look at the

information board. A couple came up the track on electric bikes

and stopped to look around. I pointed out the excellent

information board then continued walking down to the road. I was

surprised to see only one car parked by the road. I continued

back to my car near the village. |

Illustration from the information board. |

Some text from the Carrock Mines information board.

==

Mining has taken place at Carrock for over 150 years. Deep

underground, miners extracted lead, arsenic and Tungsten ores.

Over ground, the ores were crushed and washed to extract the

valuable minerals. This is the only example of a tungsten mine

in England outside Cornwall.

There are five important mineral

veins at Carrock Mine. They are called Wilson, Smith, Harding,

Waterfall and Emerson. The most important ores mined here were

Wolframite and Scheelite, which made tungsten. The Emerson vein

was the first to be worked. It is named after miner F. W.

Emerson who first mined for lead here in 1852. In the 20th

century the Harding vein was the most productive.

==

Miners often referred to tungsten as 'wolfram'. The name is said

to have come from early German miners who called it 'wolfart,

wolfert or wolfrig'. They saw that tungsten ‘ate up the tin

among which it was found as the wolf eats up the sheep’.

==

“Your wolfram is wundershön - more than wonderful - far better

than all your Lakeland scenery!”

German prospector before

World War I.

Carrock Mine was managed by two Germans, William

Boss and Frederick Boehm, from 1906 to 1912. Germany was quick

to understand the importance of tungsten and its use in making

weapons and munitions. In the early days of World War I several

'sturdy Cumbrians' mistakenly captured a geologist from the

Geological Survey at Carrock Mine. They believed he was a German

spy. They confiscated his plans and tools, 'roughed him up a

bit', reported him to the police and bundled him into the local

school room for the night.

==

The Uproar of machinery and

stir of busy endeavour

What was it like to work underground

here? George D. Abraham, author of the Complete Mountaineer

visited the mine in 1917 and described what he found:

'Wonderful crystals and rare minerals glistened in the low,

narrow, rocky walls, and now and again, when the openings to

upper galleries were passed, the songs of miners echoed in the

silent gloom. Superfluous clothing was quickly discarded, for

compared with the chilly outer air the warmth was remarkable'

from The Autocar, 27 January 1917

==

Mining stopped here

in 1981. Many of the surface remains were demolished or

flattened. In 2007 The Cumbria Amenity Trust Mining History

Society (CATMHS) began a long-term programme of surveying,

recording and managing Carrock Mine - over ground and

underground. Their work continues today. Find out more at:

www.catmhs.org.uk

== |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|